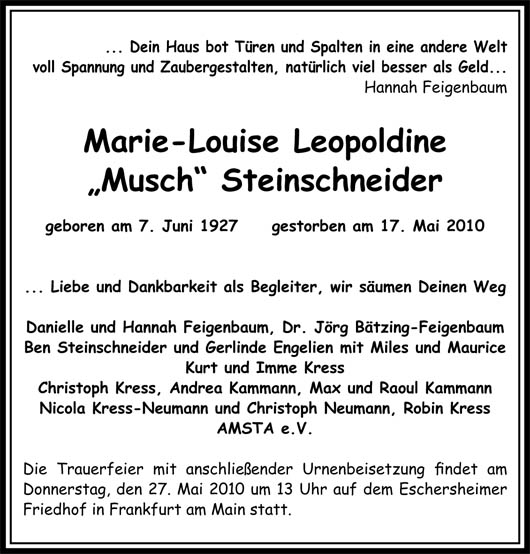

Adolf Moritz Steinschneider Archiv e.V.

Funeral oration for Musch Steinschneider

Dear Danielle and Hannah, dear Benny and Gerlinde, dear Miles and Maurice, dear mourners,

It is difficult for all of us to take leave of Musch Steinschneider in this hour. During these days of mourning one suddenly remembers a conversation with Musch that one would like to continue.

A question comes to mind that one would like to get answered. A recollection, a hint, an objection, or maybe Musch's ripe, sometimes ironic laughter, when she caught you in the midst of not being up to the mark...as the Berliners say, "nicht auf dem Damm..."

Yet, even if Musch is silent now, she will remain accessible, available, and reachable for those who were her friends. They will not only have pleasant memories of her, but Musch will somehow be communicative, ready to talk via the trail she leaves behind: the experiences she went through; her steadfastness, persistence and conscientiousness in collecting and preserving; her kindness; her humor; her knowledge; and also through the emotions we feel while mourning for her.

The house on the Altheimstrasse, where Musch lived, was an address for many people, numerous requests, and matters of interest. When I entered it for the first time some ten years ago, on behalf of the Jewish Museum in Berlin, and became aware of the memories piled up in Musch's rooms, I could only stammer, "This all is really unique!" And Musch replied self-confidently, "Yes, you are right, it is indeed!"

At Altheimstrasse No. 10, the completely unexpected maternal line of the protestant pastor Hillmann came together with the paternal side's surprising linage from Berlin's intellectual Jewry. The Steinschneider family had been made famous by father Adolf's grandfather Moritz. One was always aware of the fact that both heritages lived on in Musch.

When, in 1938, it became increasingly dangerous for Musch to stay in Nazi-Germany because of her Jewish background, mother Eva fled with her ten-year-old daughter to join her husband Adolf Steinschneider, a leftist lawyer, who had already immigrated by necessity to Paris in 1933. But exile in France offered security for only a short time.

Mother and daughter returned to Frankfurt alone after the war. Father Adolf had been killed by the SS in 1944, and Musch had further lost the great love of her youth in France; the painter Peter Grumbacher, who was deported to an extermination camp in the summer of 1942.

When taking leave of Musch today, we also commemorate the two men she lost under terror; in the rage of extermination, during the Shoa.

In Musch's rooms at Altheimstrasse, memories piled up. And they did not arrive there on their own. Musch compiled them for many, many years; assembling the material from faraway places. It was also where she nurtured concerns for her children Danielle and Benny, while pursuing her professional life, as well as her political commitments. She saved her father's manuscripts, correspondences, and documents, as well as papers and letters of her uncle Gustav Steinschneider, who had immigrated to Palestine. In this way, an unusually complex archive came into being: a unique chronicle of exile, survival, and resistance in sinister times.

Musch spoke at schools to give accounts of her ordeal. She organized lectures reading from her father's letters and initiated an exhibition of her murdered friend Peter Grumbacher's drawings. But she also remained active in continuing her father's and uncle's work; to cultivate the proud tradition of the Steinschneiders. Together with Frau Dr. Heuer she published the correspondences of her great-grandfather Moritz and his fiancé Auguste Auerbach. It's a heavy tome, but it contains many wonderfully fresh letters of two young Jewish people during the period before 1850. By reading them we also meet Musch.

Musch grew up with the clear conscience of an enlightened Jewish family tradition over many a generation. She faithfully and proudly kept that tradition all of her life and did everything in her power to cultivate it. That is what one sensed when one was fortunate enough to see her in the Altheimstrasse. And I believe that we should think, especially today, of Musch's faithfulness to a life lived in order to save all that is good and truly human; to prevent these important things from being forgotten.

Let's take leave! Let's say adieu, Musch! Let's remember Musch in love, gratefulness, faithfulness to that which she had to say, what she leaves behind for us, and the things for which she fought. Let's remember that this fight for justice in the world for Musch started in the powerlessness and threat of flight and exile.

Let's reinforce the "solidarity of the shaken ones" as André Glucksmann calls us to do in the face of the murderous 20th century, whose evil tendencies subtly remain even in the present. He was, just as Musch Steinschneider, exposed to the terror of persecution in occupied France.

(May 27, 2010, Burial in the Frankfurt-Eschersheim cemetery) Horst Olbrich

To Musch,

It was a long time ago, dear Musch. We both listened to some speech in the "Club Voltaire." How did I take notice of you and how did you attract my attention? You confronted the speaker with some grumbled arguments that sounded very human, very sensible, and very non-ideological. Listening to the ensuing discussion, I soon realized that this wasn't just an elderly woman speaking solely from her political convictions, but simply a female human being, who was accustomed to using her own head. And what a head it was! Its exterior toughness and hardness was usually softened by a somewhat odd kind of humor. But one had to gain a lot of trust before you invited him to not only contradict, but to even enter into a conversation with you-a talk. "If you are well-behaved," you said to me, "You may address me in the informal and familiar 'you'." A convincing smile emphasized those words. I wouldn't have advised anybody to turn down the offer in that situation. Furthermore, I was much too curious about further encounters.

People would use predefinitions in their descriptions of her: "Jewess," "Communist," "Survivor of the Holocaust," and "Father Murdered by the Nazis." Deep respect and reverence crept over me. Well, is that what people look like who were persecuted by the fascists, whose family had partly been murdered? There was a woman sitting in front of me whose childhood had been shaped by experiences that we could only imagine. Those experiences we knew from books, documentary films, and from court files. Those people, in my eyes, had a completely different right of being in this country than we-the "normal" citizens. Those people had not simply grown up within protected pastures. They had dwelled in the desert, where they had been exposed to the extreme weather without any protection.

You were called "Musch," you said. What a tender sound this short name had. If a child of that name is abandoned in the desert, she needs special protection, so that this child's luster remains preserved. The murder of the father, the guarded camp, and the loss of the first and tenderly cherished friend were humiliations that corroded the luster. All those and many other internal injuries of the soul and body were wounds disguised by the name Musch in the subsequent years of your life. That alone proved that the child, the young girl, the woman, knew of a love that even the most disgusting and revolting offenses had somehow not destroyed. This love had created a shell, a protective skin that became a source of power that made another life with other people possible.

And there were also the many letters of the father, the mother, and of the uncle who had succeeded in saving himself-varied evidence of a former life, which would be recounted again and again. That's what she did. And she fought for recognition of the humanistic ideas from the world of her father. She fought for his memory and that of other members of the family. So they would not be forgotten, she held on to every letter, every document; from the peaceful time of her young life to the past shaped by the War. That was the only thing she could do for her name. For that which belonged to another time was the origin of her feelings for her beloved deceased. Life afterwards was simply seen for what it was and accepted.

She never made much ado about all of the injuries from wartime. She wanted respect. She wanted to establish remembrance. She would have liked to see a book come into being that described the history of her father Adolph Steinschneider and his visions for a better world. That aim, dear Musch, you have not achieved in spite of your obstinacy, in spite of your perseverance, and in spite of the love that kept living deeply within you. You were a great fighter, Musch, and a loving daughter of your father's. We can only bow to your vitality. Yet now that I think about it, I'm strongly convinced that you'll come up with some credible arguments in heaven that will even persuade God to set up an Adolf Steinschneider Archive.

Peter Heusch, May 27, 2010

Funeral oration for Marie-Louise "Musch" Steinschneider - May 27, 2010

Dear Danielle, Ben, Gerlinde, and Jörg. Dear grandchildren Hannah, Miles, and Maurice. Dear relatives. Mourning community. Dear comrades.

We are taking leave of our mother, grandmother, and mother-in-law; of our friend and neighbor; of the antifascist and communist; of the human being Marie-Louise Steinschneider; our comrade "Musch."

She was born in Frankfurt on June 7th, 1927. Her parents were Eva Hillmann, a pastor's daughter, and the lawyer Adolf Moritz Steinschneider. Both became endangered because of their political activities; the father also because of his Jewish ancestry. Consequently, they had to emigrate. Beginning in 1938, the family of three lived in Paris in great poverty. During the war, in 1940, the family had to escape to the south of France and came to Bellac. Their meager existence in exile, the murder of Musch's father by members of the SS-division "Das Reich"--who had recently committed the massacre in Oradour sur Glane, one month before the liberation-left indelible marks on Musch's life.

In 1948 Musch returned to Frankfurt. She knew where she belonged and started her political life in the Free German Youth (Freie Deutsche Jugend/FDJ). Here, and later in the Communist Party, she openly and honestly took part in discussions and asked many unconventional, original, and uncomfortable questions.

At the performance of the Cuban duo "Ad Libitum" last year, she exclaimed, full of joy: "The fight of our parents and our own is simply right. But unfortunately, it is also still necessary!"

In spite of Musch's great illness in her last months, she continued to take part in the activities of the party: our discussions about the political situation and necessary future steps. She wanted to be informed-even in her hospital bed.

Musch had the habit of appearing at events after they had already started. But even at overcrowded gatherings, she always got a comfortable seat. On May 21st of this year, a discussion took place in Mainz during a festival with antifascist members of the resistance from the Rhein-Main-area to which Musch had also been invited. The organizers expected Musch's usual behavior-her late appearance. Instead, they received the sad news from the Frankfurt members that Musch had died on May 17th.

Dear mourning community. The poet Bertold Brecht made the effort to show economic manipulations in a drama. The protagonist of his play "Saint Joan of the Slaughter Houses," when recognizing the conditions in the abattoirs, draws the conclusion that they are no longer unchangeable, but sustained by those who draw benefit from them. Johanna exclaims, "Nothing shall be counted or considered as good, just because it looks normal, but only when it really helps; and nothing shall be considered honorable any longer unless it changes the world for the better. It needs this!"

We the comrades of the German Communist Party thank you, Musch, for your

commitment during the time that was given to you here on earth; during

which you, together with us, tried to bring about great changes. I bow

to your existence full of fighting spirit. (kämpferisches Leben-the

aggressive, combative, and pugnacious life!)

Willi Malkomes

We thank all of the friends and relatives who took leave to be with us and expressed their sympathy.

Danielle Feigenbaum and Ben Steinschneider

residential subdivision Döberitz 1911/12

the house of the Steinschneider family 2008

Steinschneiderstreet in Döberitz

Fr. 15.10.04